NECO Helped Chang Laws, Life in Teaneck

By Beverly O'Shea of the Suburbanite

A catalyst for positive change; that's the best description of what became known as NECO, the North East Community Organization.

A catalyst for positive change; that's the best description of what became known as NECO, the North East Community Organization.

It was an interracial group that drew at least 200 men and women to its regular meetings and its campaigns to maintain the quality of life during a period of social change in Teaneck about 30 years ago.

Their efforts in areas like fair housing resulted in landmark anti-blockbusting legislation shepherded through the Township Council by the first black elected to the council, Isaac McNatt, who later became a judge.

Their biggest campaign, and biggest accomplishment working with another then new organization, the Teaneck Political Assembly, was the integration of the school system.

The organization's name came from the northeast section of Teaneck where most of the blacks and African-Americans were steered in the early and mid-1960s as more started to buy homes here and move into town, mostly to get away from the problems in New York City.

"We did not want a re-occurance of what we had in New York; we wanted good sanitation, good schools, not to be neglected for township services," said Bill Witherspoon, as he and several others recalled those early days in the township and the interracial organization that worked for rights and quality of life, like good schools for their children.

The very active members, blacks and whites, lived mostly in the section between Route 4 and the Bergenfield border north of the Teaneck Armory and east from the West Shore/Conrail tracks to the Englewood border. That's where many of the real estate agents were steering people of color, although several went willingly there because they wanted to be among their own, one former NECO officer said.

NECO was concerned with the whole township. Among its projects was support for efforts to open housing in other areas of Teaneck for minority families.

Theodora Lacey recalled seeing signs on lawns that asked, "Have you looked elsewhere?"

Many black families were drawn here, Witherspoon recalled, because of a booklet that called Teaneck "one of the most democratic and outstanding" communities in the area. They found they liked the idea of a council-manager form of government, Witherspoon added, "not Democrats and Republicans, but people who stood for the town's growth."

Regarding NECO's concern with the entire township, many of the members interviewed recalled that whenever they had their annual dance, they drew a big townwide crowd, and everybody had fun and enjoyed being with one another.

The 1960s was a time of real white flight, when families unused to living in the same neighborhood with persons of other races became afraid of the change and decided they could not cope.

Byron Whitter recalled that white families - some who had sworn never to leave the area - had even moved out in the middle of the night, apparently so they did not have to face questions from their neighbors.

Byron Whitter recalled that white families - some who had sworn never to leave the area - had even moved out in the middle of the night, apparently so they did not have to face questions from their neighbors.

"You'd go to bed at night and they were there, and you'd wake up in the morning and their house would be empty,' he said.

Whitter estimated that his street had changed from predominantly white families to predominantly black in less than two years.

Witherspoon said only a few black families were in the area when he and his family moved here in 1961. He even recalled the little boy who was the first black to enter kindergarten at Bryant School, then the neighborhood school for the area.

One of the NECO campaigns involved persuading other white families to move into the area, to replace some of those leaving. Tasha Morton, a retired teacher and current Board of Education member, and her husband Richard, with their two children, decided to buy their first house there. Explaining they wanted to help "stabilize the community," she became very active in the organization.

Theodora Lacey, a teacher whose late husband Archy was also very active, remembers many planning meetings in their home, but the first organizational meeting was in Bryant School.

Civil rights activists since Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. started the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott in 1955 from her family's church, Lacey and her husband were among the first dozen parents who agreed to send their children to schools outside the northeast district. They were trying to initiate voluntary integration, but NECO members said they soon realized that would not work.

Thomas Boyd, who later became a councilman and Board of Adjustment chairman, was the organization's first chairman. Both Lacey and Boyd, who was interviewed by telephone at his new home in Columbia, S.C., remembered that NECO started in 1964. It was after the March on Washington, Lacey said, and it was before the Teaneck Board of Education vote that led to using Bryant as a central sixth-grade school and busing neighborhood students to other schools in town.

Boyd said some had also proposed the idea of pairing schools to assist integration, Washington Irving with Eugene Field and Bryant with Whittier. "But we felt it was extremely important to deal with each other in the whole town.

That's when the push for integration, not based on volunteer families but on a townwide decision for integration, began, Boyd said.

NECO went on to become active in other ways, networking through Boyd and Lacey and others, with the PTA, but maintaining its independence.

"It was actually a catalyst that drew people together," said Whitter, who was also a NECO president. "It was the mechanism for approaching people, because whites were not used to dealing with blacks who spoke up."

Leon Gilchrist was president between Boyd and Whitter.

Whitter described the school integration battle as "a bitter struggle in town." After the Board of Education agreed to the integration plan, NECO worked hard to help make it work, although many agreed the first effort, the central sixth grade school, was not the way to go.

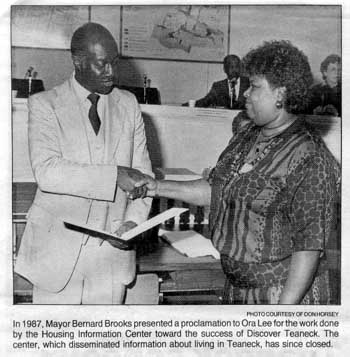

The group was successful in getting McNatt, who has since retired to North Carolina, elected to the Township Council. One of the projects they could not attain, McNatt recalled, was to elect McNatt and later Bernard Brooks, Teaneck's first black mayor, to the Bergen County Board of Chosen Freeholders.

Some, like former Bergen County NAACP President George Powell, had to fight to buy a home west of the railroad tracks. But he was able to stay, and other minority families currently own homes throughout the township.

Witherspoon was the first black on the township's Board of Adjustment, preceding Boyd. Later, Witherspoon's wife, Carolyn, also served on that board.

The organization operated for about a dozen years, but few could pin down why it faded away. Boyd said he wished it had not, because it would have been a force to be reckoned with on other issues.

Witherspoon said he thought people started backing away when the political parties started to carry on the campaigns begun by NECO.

Whitter thinks the problem stemmed from an erosion of leadership, when others did not fill in to follow the organizers.

Some theorized that NECO might have been involved in the current campaign to eliminate what is perceived as racial disparities in the schools, although they were not sure that it would have gone as far as the federal civil rights complaint filed by the Coalition for Equity Education.